Sign up to Miguel Delaney’s Reading the Game newsletter sent straight to your inbox for free

Sign up to Miguel’s Delaney’s free weekly newsletter

Thanks for signing up to the

Football email

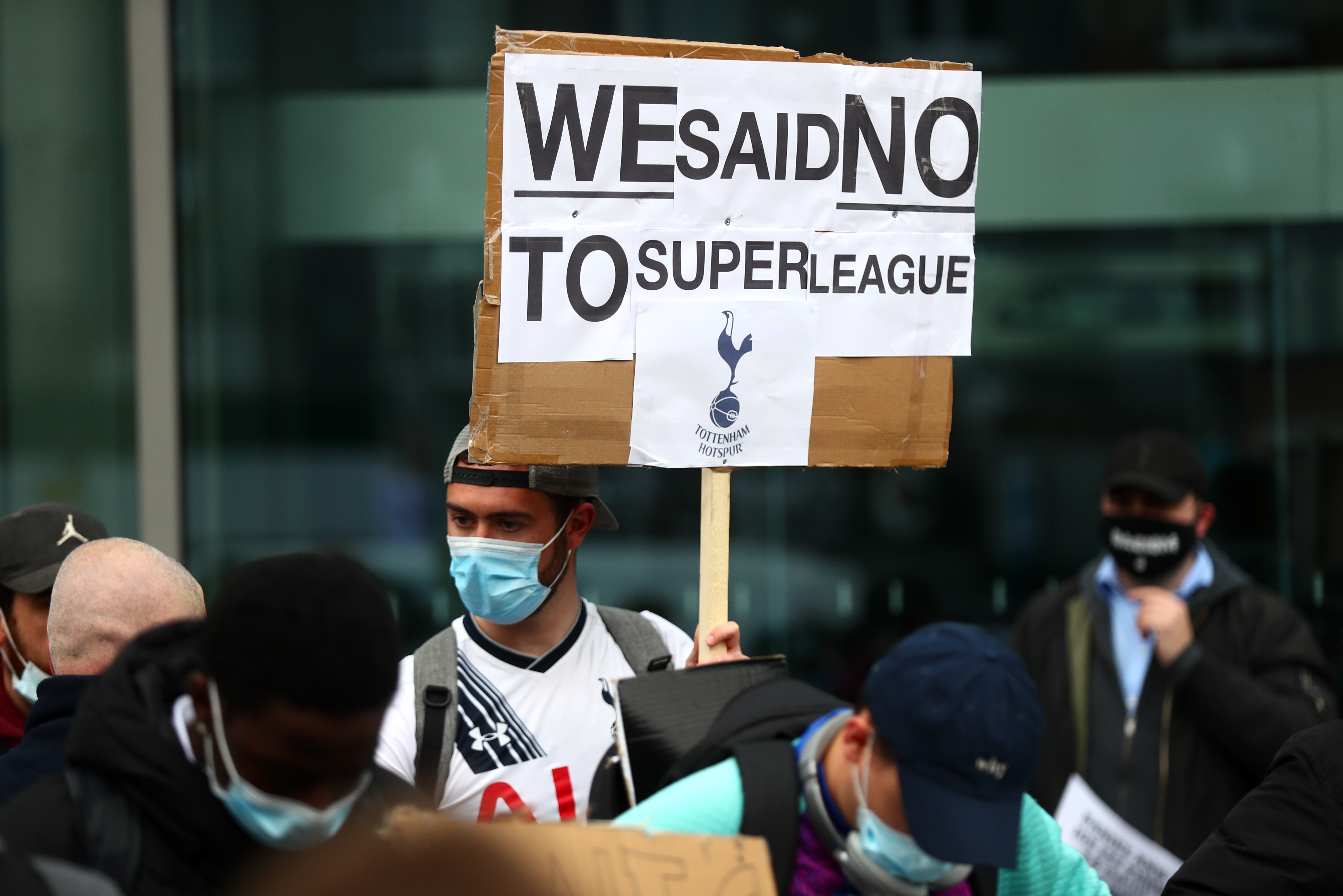

If it seems strange that there is still so much talk of the European Super League given what happened in April 2021, there are many involved in the case now that are making even grander statements about it all.

They believe that Thursday is “bigger than Bosman”. That will be the day the entire episode either comes to a conclusion or a new start. The European Court of Justice [ECJ] will rule on whether bodies like Uefa and Fifa represent monopolies that must be broken up, or if that structure is necessary for the running of football. It all stems from the case the Super League planners took around the time of its launch.

Put in simple terms, this will decide whether they can get the project properly going again, and change the face of European football.

Thursday will also see two connected cases decided, making it a potentially landmark day in sport legislation. Those very words might sound dismally dry but the outcome will determine what the football we watch will actually look like. We will know whether the Champions League can be the same; whether the sport as a whole will stay a unified pyramid or potentially disperse into the same sort of chaos as boxing.

As regards the actual teams that clubs can put out, one of the decisions will rule on whether Uefa’s regulations on homegrown players contradict EU law, from a case brought by Royal Antwerp. Another will involve the International Skating Union and all of the same themes as in football. This is whether a restriction on events organised by other parties also represents a restriction of competition.

The core of all this is something universal, that has warranted resolution since the very foundation of organised sport, and particularly since the involvement of the European Union. It is about the tension between football as a business and football as a sport.

The Super League clubs are fundamentally trying to argue that it is just an “entertainment industry” that should be subject to the same rules as any such company. Uefa are trying to argue it is a cultural pursuit that warrants special protections.

A problem has long been that the latter was never stated in law, which led to the monumental Bosman ruling wreaking such havoc on the economy of football. It created an almost completely open market and scores of unintended consequences. A recognition of this in the last few years has led to something closer to a legal articulation, as well as Advocate General Athanasios Rantos’ recommendation to the ECJ last December that the status quo should actually be strengthened.

There are a number of other influential current themes swirling around this and influencing it. Among them are whether the European football model currently works; the power of the Premier League against everyone else and Fifa’s ongoing attempts to control the transfer market through limits on the influence of agents. That last issue is where the homegrown player decision is potentially big, since Fifa may now seek to go in this direction to impose controls on the market.

The Super League’s latest pitch has meanwhile been to play on legitimate concerns over where European football is going, and how so few teams outside England can actually compete. This is what may well prove attractive to big-city clubs from smaller markets – from Ajax to Sparta Prague – should they win.

It is why, although this will ultimately come down to the letter of the law and attempt to unify theories on how sport fits into laws on competition and free movement, there is going to be a lot of spin on Thursday. Both sides will seek to declare victory no matter what happens.

Along the same lines, the Super League have long attempted to present their case as the under-resourced rebellion taking on the all-powerful establishment. They have even hired Jean-Louis Dupont, who has been a specialist in such football cases. There are many in the sport who find that laughable. The entire project is still being driven by Real Madrid president Florentino Perez. Similarly, despite the presence of Dupont, he is seen as a little more than a sidekick here for “magic circle” law firm, Clifford Chance. The Super League’s legal case is being led by their Madrid corporate department and Luis Alonso, who have a strong relationship with the Bernabeu president. It is why many quip about “the House of Perez”.

The main thrust of the Super League’s argument is that Uefa have an “astonishing” set of powers, that is a relic from an era that no longer serves modern sport. The position is that Uefa are governing body, regulator, commercial operator and gatekeeper, who also have huge sanctioning powers. This, the Super League would argue, is why the project has had to be so secretive about the next stage of their plans. They don’t want to get potential members in trouble.

It is actually a position that is gaining credence in Europe. Legitimate governance concerns about Uefa’s executive presidential model shouldn’t be discounted, either. One of the most common lines in continental football right now is “something must be done about the Premier League”. This is potentially that something, even if the true effect would be the end of the Champions League as we know it. Many would argue it no longer works, since Uefa have overseen a system that has left most of Europe – including some huge cities – a football wasteland.

They believe a huge opportunity is being squandered to make European football the undisputed pinnacle of world sport, way above anything else given its global popularity.

The Super League will consequently present any break-up of Uefa’s powers as a victory. They believe this will give them opening, even if it takes a long time to get to where they want. There is notable confidence they will at least get that, and the ability for clubs to explore other options.

There is as much confidence on the other side. They would point to how 23 EU member states turned up to back Uefa when this was being heard. Nobody has yet been able to find a previous case that comes close to that. When the ECJ was ruling on the legality of the member-state bail-outs amid the banking crisis, only 11 joined to support Ireland.

That is how much the idea of sport matters. The Super League instead cast that support as a show of how much Uefa going to extreme lengths to suppress dissent.

This still has to come down to specific legal terms, though, and Uefa’s lawyers have been making an argument on authorisation rules. That would after all appear to be one of the key points of the Super League case, since they are making the argument over the creation of competitions. If so, they might have already lost. A reassessment of the rules was already under way before the Super League was launched, and has been central to the skating case. A huge irony is that Andrea Agnelli, one of the main architects of the Super League through his presidency of Juventus, would have had access to all information on this when he sat on the Uefa Executive Committee. That is mostly a point of detail, though.

The Super League have really been approaching it on the long-running philosophical argument that football is just business, but this may now force the issue into law either way.

Uefa’s lawyers are hopeful that will mean the ECJ protecting sport as a cultural pursuit. They feel this has been the direction of travel, despite debate about the much-discussed article 165, which notionally covers the role of sport. Rantos was clearly heading that way, that it’s time to legally make sport part of the fabric of the EU.

The argument on that side is that the entire Super League, even in its new form, represents a disdain for the pyramid and just a way to remove Uefa. They also indicate the added danger that, while it might just put power into the hands of the clubs now, there’d be nothing stopping future developments like selling off the pervading sports model to private equity.

It’s not even like the clubs represent the best option. The European “wasteland” is largely the result of the world clubs like Madrid and Barcelona created. They pushed for every advantage for so long it cannibalised the rest of the sport. Spain and its “wasted decade” of distorted TV rights are put forward as a classic example. It still has an effect now.“You could give Barcelona £1bn and it’s still hard not to believe they’d still just spend it on players,” one source says.

The Super League have themselves been looking to some of the arguments made on article 165 in the Antwerp case, and how it’s been presented as soft law. It is viewed as entirely possible that the ECJ rule against Uefa there. The premise is that it could represent indirect discrimination for players developed in the same national federation to be considered “homegrown”. That rule is in place so, if a young player moves from Stoke City to a club an hour away like Manchester United, say, they don’t lose their “homegrown” status. If that is ruled against, it still might have the opposite effect than intended. It could mean Uefa clubs just have to name more directly homegrown players in their squad, as the ECJ advisor suggested in advance of the ruling. That in itself may bring a potential solution for Fifa in their attempts to reform the transfer market. Either way, it would seem highly unlikely that the ECJ offers any ruling that goes against the incentivisation of training.

Again, all of this may seem very dry. It it is crucial, however, because it will directly shape the football we watch. It isn’t just about what the sport will look like. It’s about what the sport means.

Source: Read Full Article